Car Guides & Features

At Vanarama we want you to find your New Lease Of Life and we want to make sure it’s the perfect one for you! So, if you’re looking for a brand new car, whether for business or personal use, you’ve come to the right place. We’ll show you just how easy car leasing is and we’ve also rounded up the latest colour guides, comparison features and how-to guides from auto experts Mark Nichol and Matt Robinson so you can find your dream car today.

Whether you need space for a big family or just want a comfortable ride for long journeys, we've got you covered! Discover the top picks and find the perfect MPV or people carrier for your needs.

Safety and reliability are two of the main things you want from your family car, so take a look at Vanarama’s rundown of 10 of the best today.

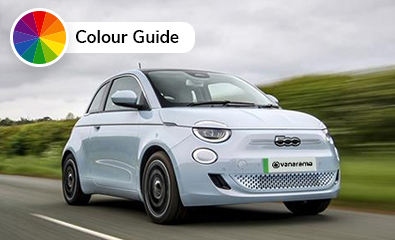

Here’s a detailed look at the paint palette available on the Fiat 500 4-seater city electric vehicle (EV), which we hope will help you choose your perfect new car colour...

Need a little help finding your perfect family car? Get advice from the experts and check out Vanarama’s guide to the best family SUVs for 2023.

Here’s a detailed look at the paint palette available on the Audi Q5 5-door, 5-seater SUV which we hope will help you choose your perfect new car colour...

2022 brings the launch of the Tesla Model Y. Which is essentially a crossover SUV version of the Model 3. So, what’s the difference between them? Should you wait for the Y before placing an order for the 3? Let’s dig into it…

Here’s a detailed look at the paint palette available on the Tesla Model Y 5-seater electric SUV, which we hope will help you choose your perfect new car colour.

Looking for a small car but can't choose between the Fiat 500 and Vauxhall Corsa? We put the two head-to-head...

Here’s a detailed look at the paint palette available on the Vauxhall Corsa 5-seater supermini, and its all-electric derivative in the form of the Corsa-e, which we hope will help you choose your perfect new car colour.